Weyl group

| Lie groups |

|---|

|

General linear group GL(n)

Special linear group SL(n) Orthogonal group O(n) Special orthogonal group SO(n) Unitary group U(n) Special unitary group SU(n) Symplectic group Sp(n) |

In mathematics, in particular the theory of Lie algebras, the Weyl group of a root system Φ is a subgroup of the isometry group of the root system. Specifically, it is the subgroup which is generated by reflections through the hyperplanes orthogonal to the roots, and as such is a finite reflection group. Abstractly, Weyl groups are finite Coxeter groups, and are important examples of these.

The Weyl group of a semi-simple Lie group, a semi-simple Lie algebra, a semi-simple linear algebraic group, etc. is the Weyl group of the root system of that group or algebra.

It is named after Hermann Weyl

Contents |

Examples

For example, the root system of A2 consists of the vertices of a regular hexagon centered at the origin. The Weyl group of this root system is a subgroup of index two of the dihedral group of order 12. It is isomorphic to S3, the symmetric group generated by the three reflections on the main diagonals of the hexagon.

Weyl chambers

Removing the hyperplanes defined by the roots of Φ cuts up Euclidean space into a finite number of open regions, called Weyl chambers. These are permuted by the action of the Weyl group, and it is a theorem that this action is simply transitive. In particular, the number of Weyl chambers equals the order of the Weyl group. Any non-zero vector v divides the Euclidean space into two half-spaces bounding the hyperplane v∧ orthogonal to v, namely v+ and v−. If v belongs to some Weyl chamber, no root lies in v∧, so every root lies in v+ or v−, and if α lies in one then −α lies in the other. Thus Φ+ := Φ∩v+ consists of exactly half of the roots of Φ. Of course, Φ+ depends on v, but it does not change if v stays in the same Weyl chamber. The base of the root system with respect to the choice Φ+ is the set of simple roots in Φ+, i.e., roots which cannot be written as a sum of two roots in Φ+. Thus, the Weyl chambers, the set Φ+, and the base determine one another, and the Weyl group acts simply transitively in each case. The following illustration shows the six Weyl chambers of the root system A2, a choice of v, the hyperplane v∧ (indicated by a dotted line), and positive roots α, β, and γ. The base in this case is {α,γ}.

Coxeter group structure

Weyl groups are examples of finite reflection groups, as they are generated by reflections; the abstract groups (not considered as subgroups of a linear group) are accordingly finite Coxeter groups, which allows them to be classified by their Coxeter–Dynkin diagram.

Concretely, being a Coxeter group means that a Weyl group has a special kind of presentation in which each generator xi is of order two, and the relations other than xi2 are of the form (xixj)mij. The generators are the reflections given by simple roots, and mij is 2, 3, 4, or 6 depending on whether roots i and j make an angle of 90, 120, 135, or 150 degrees, i.e., whether in the Dynkin diagram they are unconnected, connected by a simple edge, connected by a double edge, or connected by a triple edge.

Weyl groups have a Bruhat order and length function in terms of this presentation: the length of a Weyl group element is the length of the shortest word representing that element in terms of these standard generators. There is a unique longest element of a Coxeter group, which is opposite to the identity in the Bruhat order.

Example

The Weyl group of the Lie algebra  is just the symmetric group on

is just the symmetric group on  elements,

elements,  . The action can be realized as follows. If

. The action can be realized as follows. If  is the Cartan subalgebra of all diagonal matrices with trace zero, then Sn acts on

is the Cartan subalgebra of all diagonal matrices with trace zero, then Sn acts on  via conjugation by permutation matrices. This action induces an action on the dual space

via conjugation by permutation matrices. This action induces an action on the dual space  , which is the required Weyl group action.

, which is the required Weyl group action.

Definition

The Weyl group can be defined in various ways, depending on context (Lie algebra, Lie group, symmetric space, etc.), and a specific realization depends on a choice – of Cartan subalgebra for a Lie algebra, of maximal torus for a Lie group.[1] The Weyl groups of a Lie group and its corresponding Lie algebra are isomorphic, and indeed a choice of maximal torus gives a choice of Cartan subalgebra.

For a Lie algebra, the Weyl group is the reflection group generated by reflections in the roots – the specific realization of the root system depending on a choice of Cartan subalgebra (maximal abelian).

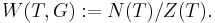

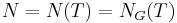

For a Lie group G satisfying certain conditions,[note 1] given a torus  (which need not be maximal), the Weyl group with respect to that torus is defined as the quotient of the normalizer of the torus

(which need not be maximal), the Weyl group with respect to that torus is defined as the quotient of the normalizer of the torus  by the centralizer of the torus

by the centralizer of the torus

The group W is finite – Z is of finite index in N. If  is a maximal torus (so it equals its own centralizer:

is a maximal torus (so it equals its own centralizer:  ) then the resulting quotient

) then the resulting quotient  is called the Weyl group of G, and denoted

is called the Weyl group of G, and denoted  Note that the specific quotient set depends on a choice of maximal torus, but the resulting groups are all isomorphic (by an inner automorphism of G), since maximal tori are conjugate. However, the isomorphism is not natural, and depends on the choice of conjugation.

Note that the specific quotient set depends on a choice of maximal torus, but the resulting groups are all isomorphic (by an inner automorphism of G), since maximal tori are conjugate. However, the isomorphism is not natural, and depends on the choice of conjugation.

For example, for the general linear group GL, a maximal torus is the subgroup D of invertible diagonal matrices, whose normalizer is the generalized permutation matrices (matrices in the form of permutation matrices, but with any non-zero numbers in place of the '1's), and whose Weyl group is the symmetric group. In this case the quotient map  splits (via the permutation matrices), so the normalizer N is a semidirect product of the torus and the Weyl group, and the Weyl group can be expressed as a subgroup of G. In general this is not always the case – the quotient does not always split, the normalizer N is not always the semidirect product of N and Z, and the Weyl group cannot always be realized as a subgroup of G.[1]

splits (via the permutation matrices), so the normalizer N is a semidirect product of the torus and the Weyl group, and the Weyl group can be expressed as a subgroup of G. In general this is not always the case – the quotient does not always split, the normalizer N is not always the semidirect product of N and Z, and the Weyl group cannot always be realized as a subgroup of G.[1]

Bruhat decomposition

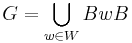

If B is a Borel subgroup of G, i.e., a maximal connected solvable subgroup and a maximal torus  is chosen to lie in B, then we obtain the Bruhat decomposition

is chosen to lie in B, then we obtain the Bruhat decomposition

which gives rise to the decomposition of the flag variety G/B into Schubert cells (see Grassmannian).

The structure of the Hasse diagram of the group is related geometrically to the cohomology of the manifold (rather, of the real and complex forms of the group), which is constrained by Poincaré duality. Thus algebraic properties of the Weyl group correspond to general topological properties of manifolds. For instance, Poincaré duality gives a pairing between cells in dimension k and in dimension  (where n is the dimension of a manifold): the bottom (0) dimensional cell corresponds to the identity element of the Weyl group, and the dual top-dimensional cell corresponds to the longest element of a Coxeter group.

(where n is the dimension of a manifold): the bottom (0) dimensional cell corresponds to the identity element of the Weyl group, and the dual top-dimensional cell corresponds to the longest element of a Coxeter group.

Analogy with algebraic groups

There are a number of analogous results between algebraic groups and Weyl groups – for instance, the number of elements of the symmetric group is  , and the number of elements of the general linear group over a finite field is the q-factorial

, and the number of elements of the general linear group over a finite field is the q-factorial ![[n]_q!](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4068da6f34e0edc79705024cdc294e3d.png) ; thus the symmetric group behaves as though it were a linear group over "the field with one element". This is formalized by the field with one element, which considers Weyl groups to be simple algebraic groups over the field with one element.

; thus the symmetric group behaves as though it were a linear group over "the field with one element". This is formalized by the field with one element, which considers Weyl groups to be simple algebraic groups over the field with one element.

Cohomology

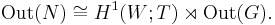

For a non-abelian connected compact Lie group G, the first group cohomology of the Weyl group W with coefficients in the maximal torus T used to define it,[note 2] is related to the outer automorphism group of the normalizer  as:[2]

as:[2]

The outer automorphisms of the group Out(G) are essentially the diagram automorphisms of the Dynkin diagram, while the group cohomology is computed in (Hämmerli, Matthey & Suter 2004) and is a finite elementary abelian 2-group ( ); for simple Lie groups it has order 1, 2, or 4. The 0th and 2nd group cohomology are also closely related to the normalizer.[2]

); for simple Lie groups it has order 1, 2, or 4. The 0th and 2nd group cohomology are also closely related to the normalizer.[2]

Notes

- ^ Different conditions are sufficient – most simply if G is connected and either compact, or an affine algebraic group. The definition is simpler for a semisimple (or more generally reductive) Lie group over an algebraically closed field, but a relative Weyl group can be defined for a split Lie group.

- ^ W acts on T – that is how it is defined – and the group

means "with respect to this action".

means "with respect to this action".

References

- Popov, V.L.; Fedenko, A.S. (2001), "Weyl group", Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, SpringerLink, http://eom.springer.de/W/w097710.htm

- Hämmerli, J.-F.; Matthey, M.; Suter, U. (2004), "Automorphisms of Normalizers of Maximal Tori and First Cohomology of Weyl Groups", Journal of Lie Theory (Heldermann Verlag) 14: 583–617, http://www.heldermann-verlag.de/jlt/jlt14/mattla2e.pdf